found: http://nolabounce.com

Matt Miller – Second Line Jump

Posted by emynd on | September 26, 2010 | 4 Comments

SECOND LINE JUMP: NEW ORLEANS RAP AND BRASS BAND MUSICWords and Mix By Matt Miller (millernarian@gmail.com)

September 27, 2010

“New Orleans is young kids, dudes that’s jazz musicians and none of them read music but all of them picked up something and they perfected it. You could go see that 24-7 and now that is not there no more… You get inspiration from going to see somebody else do something. Like if I want to go see a jazz band or whatever, that’s inspiration for me, that makes me want to go home and do some jamming shit.”

– Mannie Fresh, Interviewed by Noz for Cbrap.com

Over the last thirty years, New Orleans rappers and producers have used various techniques to put a local stamp on their music. In the realm of lyrics, the city’s urban geography and the distinctive traditions and practices of its African American residents provided ample subject material for rappers. Musically, rappers and producers experimented with and refined ideas that resonated with local audiences, helping to define New Orleans rap and make it distinct from that coming from other places. These musical elements included particular phrases or patterns within the vocal performance, certain ways of structuring beats, and a core group of widely-used samples, including those from “Drag Rap” that became a hallmark of bounce in the 1990s.

My focus in this article is on a particular subset of these multiple ways of signifying the local in New Orleans rap—the intersections between rap and brass band music, including the use of sampled or recorded brass within local rap production and rappers performing in front of a live band. While brass band and second line samples and collaborations are only one of many ways to represent “New Orleans” in rap, they remain some of the most compelling and unique expressions of New Orleans’s ability to embrace both innovation and tradition simultaneously. The propulsive and dynamic music of the city’s many brass bands has served as a resource of local sound and attitude that meshed remarkably well with rap music, a fact that underscores the deep connections between rap and the Afro-Caribbean heritage and sensibility of New Orleans. Conversely, brass bands—especially those made up of younger men for whom rap and hip-hop form a major part of their musical diet—have incorporated influences from local and national hip-hop, alternating between traditional standards and popular hits to keep their audience’s attention.

Hit the jump for the rest of the article, tracklisting, and download link!

The brass band tradition of New Orleans dates back to the last decades of the 19th century, when the city’s African American communities, drawing on traditions of organization, education, and self-reliance, initiated performance and instruction on brass and string band instruments. The numerous black bands from New Orleans and its hinterlands formed one of the core influences upon the emergence of jazz. The smaller ensembles that defined the new jazz form, often led by street-savvy “American” blacks like Buddy Bolden and Chris Kelly, pioneered the new “hot” way of playing and introduced notions of collective improvisation and the elaboration and transformation of existing songs and melodies. Their presence was too loud and boisterous to be ignored, especially when bands met in competitive expositions and musicians pulled out all of the stops in order to win the crowd’s favor.

New Orleans’s dominant position in the world of jazz faded in the 1930s, but marching brass bands remained a staple of local music culture. In the interwar and postwar eras, legendary bands like Dejan’s Olympia and the Eureka Brass Band carried on the tradition. In New Orleans, the parading brass band—mobile and often audible for great distances—has been an enduring symbol of African American influence in the city’s public culture.

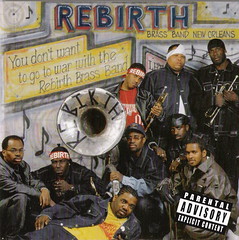

By the 1970s, however, the brass band form had become semi-moribund, an archaic remnant of jazz-age New Orleans culture. However, new generations of musicians transformed the genre, infusing it with the energy and techniques of contemporary African American forms like soul and funk. The Dirty Dozen was the first of these funky brass bands; other bands that followed, including Rebirth, made further contributions to the shaping of a fresh and dynamic sensibility in the genre over the past three decades.

The number of brass bands has expanded along with the proliferation of “second Line” clubs, so-called “social and pleasure” organizations which hire bands for parades. These clubs stage parades on Sunday afternoons throughout the second line “season” (which spans much of the Fall, Winter and Spring), often to celebrate the anniversary of the club’s founding. These second line parades, along with the “jazz funerals” and Mardi Gras parades that often define New Orleans in the national imagination, serve as a central venue for brass bands and play a key role in disseminating and reinforcing a commonly-held musical sensibility. To outsiders, second line parades might seem like a purely celebratory event, but they can also channel more destructive energies. The bands are often joined by a rowdy group of spontaneous participants (often teenagers or young men) who contribute highly expressive dance and ad-hoc music-making. “Buck jumping,” an individual dance form associated with both brass bands and local rap, is one of the many features of New Orleans’s musical culture that in concept and nomenclature can be traced back to the 19th century and the era of slavery.

Rappers and producers, along with other African Americans who grew up poor or lower middle-class in New Orleans, frequently took advantage of the free, public entertainment offered by second line clubs and the brass bands they hired. Many individuals involved in the New Orleans rap scene have enjoyed deep connections to brass bands and second line groups, which have frequently led to artistic collaborations. Local legend Warren Mayes, best known for the 1989 hit , “Get It Girl”, had ties to Rebirth, among other brass bands. In his role as club owner and promoter, Mayes often drew upon these connections to put together impressive bills like “Summer Jam ’92” , which featured Rebirth along with a host of local rap luminaries. On his 1994 CD “Canivin Boys,” he included several songs by Rebirth, including a short rendition of “Get It Girl” (retitled “You Make Me Nasty” after the song’s chanted refrain) as well as another where Mayes performed vocals over the band’s music. James “Soulja Slim” Tapp’s stepfather Philip Frazier plays tuba for the legendary ReBirth band (his mother, Linda Tapp Porter, has been active in the Lady Buck Jumpers second line club).

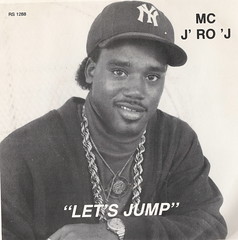

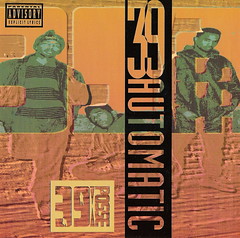

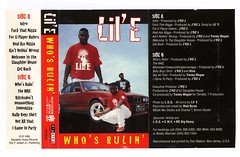

Used as a lyrical subject, second line culture was present in local New Orleans rap as early as 1983, when the group Parlez released their single “Make It, Shake It, Do It Good” (subtitled “Mardi Gras Man”). The idea of sampling or replaying brass band music within rap production was introduced in MC J’ Ro J’s 1988 single on Rosemont, “Let’s Jump,” which used multiple samples from Rebirth’s 1984 debut, Here to Stay. J’ Ro J’ (Roy P. Joseph, Jr.) continued to show an interest in the possibilities of combining rap and second line music in his production of songs by the Bally Boyz and Lil’ E for his Slaughterhouse Records label. The group 39 Posse, which featured future No Limit producer Craig “KLC” Watkins, made a splash on the local scene with a song, “Got What it takes to Make It,” which used a sample from Rebirth’s catchy 1989 song “Feel Like Funkin It Up.” The same melody was also used in local rap songs by Da’ Sha Ra’ (“Bootin’ Up”), Ricky B (“Y’all Holla”) and Big Heavy (“Gangsta Walk”). Over the course of the 1990s, several rappers collaborated with brass bands in recordings, including Joe Blakk and Rebirth’s “Caught in the Crossfire” and the 2001 Rebirth album of local favorites, Hot Venom, which featured appearances by Soulja Slim (“You Don’t Want to go to War”) and Cheeky Blakk (“Pop that Pussy”).

While the “golden age” of rap-brass band collaboration may have passed, the combination remains a compelling example of the connections between second line culture and local rap in New Orleans. However, there are other, less obvious, lines of influence. Exposure to brass band music may be responsible for the melodic qualities that often mark the vocal performances of New Orleans rappers, while the chanted, collective vocals of brass bands have been easily adapted into the rap form. The attitudes of second line and brass band parading have also blended well with the concerns and ideas of the rap era. The celebratory nature of brass band parades coexist with a territorial toughness, as onlookers or other bands are told to “get out the way” and are warned, “Don’t start no shit, won’t be no shit.” Like brass band music and second line parades, local rap contributes to a collectively-held musical and cultural sensibility at the same time that it serves as a venue and catalyst for competition and animosity between local groups. Independently and in combination with each other, local rap and second line music express the city’s dynamic and vital traditions and contribute to the uniqueness of its cultural and musical environment.

Click on the link below to download a continuous mix of New Orleans rap and brass band music, or listen to the stream above.

Second Line Jump: New Orleans Rap and Brass Band Music — Compiled and Mixed by Matt Miller (Mediafire Download)

Tracklist:

Rebirth & Warren Mayes, “Let It Hang” (1994)

Big Heavy, “Gangsta Walk II” (1996)

MC J’ Ro J’, “Let’s Jump” (1988)

Rebirth & Soulja Slim, “You Don’t Want to Go to War” (2001)

Da’ Sha Ra’, “Bootin’ Up” (1993)

Ricky B, “Ya’ll Holla” (1994)

2 Blakk, “Second Line Jump” (1995)

Rebirth & Cheeky Blakk, “Pop that Pussy” (2001)

Bally Boyz, “Send It” (Raw) (1995)

Big Heavy & New Birth Brass Band, “Leave that Shit Alone” (1996)

Joe Blakk & Rebirth, “Caught in the Crossfire” (???)

Big Heavy, “Gangsta Walk” (1992)

Ricky B., Mannie Boo & the Mac Band “Let’s Go Gitt’em” (1996)

Rebirth, “You Make Me Nasty” (1995)

39 Posse, “Got What It Takes to Make It” (Remix) (1993)

Gregory D. & Mannie Fresh, “Buck Jump Time (Project Rapp)” (1989)

Lil’ E, “Get Buck” (1995)

Thanks to all the rappers, producers, musicians, brass bands, second line groups, and New Orleans in general. Special thanks to Noz, Colin Meneghini, Jib Kidder, Joe Blakk, Dartanian Stovall.

[Bio: Matt Miller is the co-director of the documentary film Ya Heard Me? and completed his Ph.D. dissertation, “Bounce: Rap Music and Local Identity in New Orleans, 1985-2005,” in August of 2009 at Emory University’s Graduate Institute of the Liberal Arts. He currently lives in Atlanta.]

No comments:

Post a Comment